Local police squad “buncoists” lead charge against hacks, soothsayers, and “buncos”

Police Bunco Squads aim to protect the public from sinister “gags” and fraudulent activities

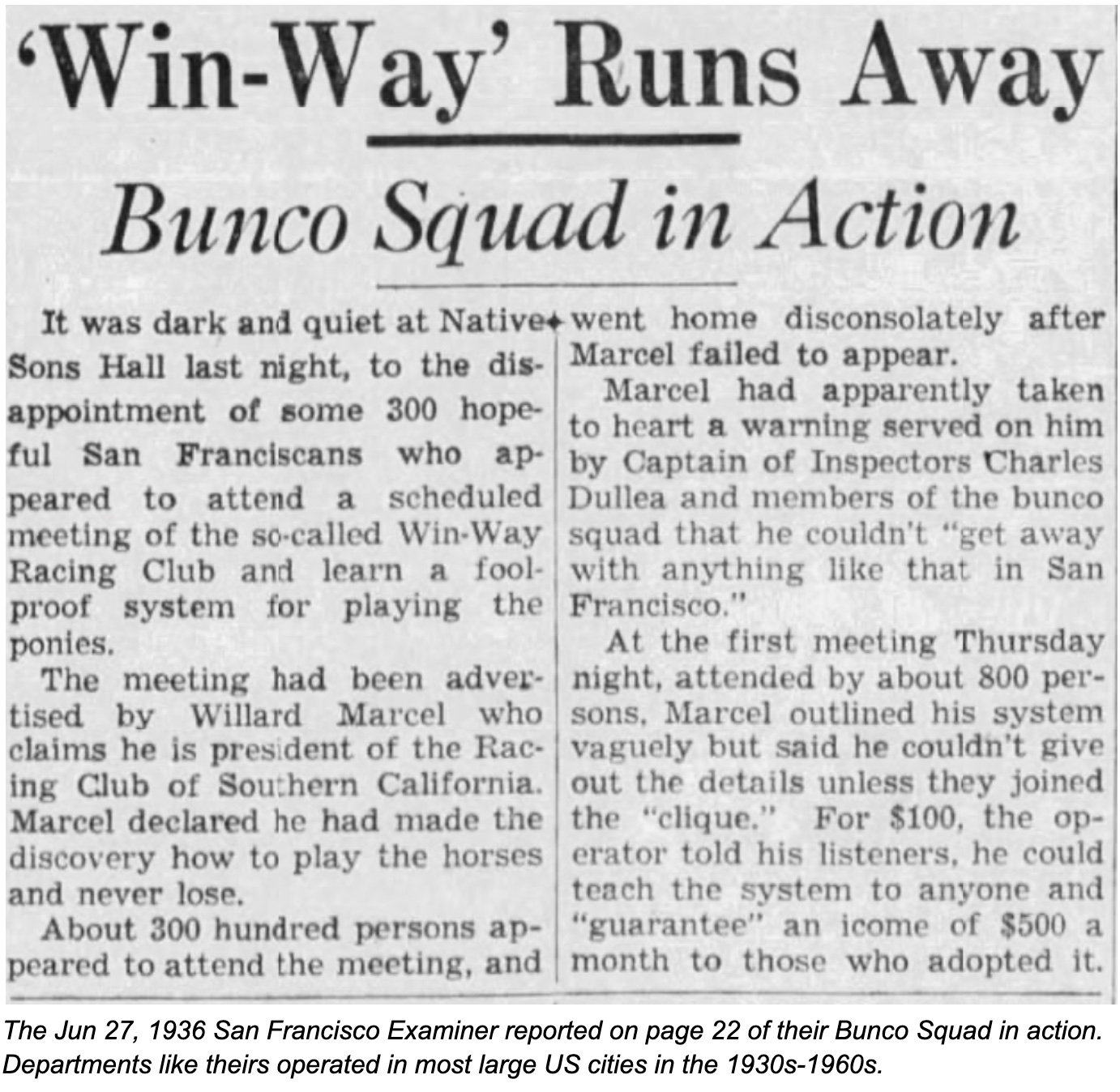

The Jun 27, 1936 San Francisco Examiner reported on page 22 of their Bunco Squad in action. Departments like theirs operated in most large US cities in the 1930s-1960s.

The Jun 27, 1936 San Francisco Examiner reported on page 22 of their Bunco Squad in action. Departments like theirs operated in most large US cities in the 1930s-1960s.

On a chilly day in November 1943 two men approached an older man known as Dominic to locals. Dominic was sitting outside the Civic Center in Long Beach, California.

“Gentlemen,” one of the strange men said, nodding with the brim of his cap.

“Afternoon,” replied Dominic. “What do you have there?”

“This? It’s my money-making machine,” replied one stranger. The other, dressed in a fine suit and wide-brimmed hat, stopped and smiled.

Curious, Dominic leaned forward. “What do you mean, a money-making machine?” He asked. Being too old for work, the Great Depression was challenging. But with little family or other obligations, Dominic had carefully saved over $10,000. His life savings, worth about $182,000 in 2024 dollars, was tucked in his personal belongings and not in the bank. The banks had lost too much money over the last ten years.

The men chatted amicably with Dominic for a while, listening to his stories and showing the anxious man their money-making machine. The machine, pre-stuffed with fives and tens, was a crude metal and wood contraption that cranked out bills with the turn of a gear. Time and time again, Dominic asked to see it in action only to find the strangers eager to turn the crank, pull out a $5 bill, and pocket the cash before his eyes.

Within a careful buildup over 10 minutes, Dominic insisted he buy this world-changing money-making machine. With little thought to how it worked or the inflation risks if every American possessed their own printing press, he handed over all his $10,000 in savings. The men, feigning worry over the sale, hesitantly agreed and handed it over.

Dominic cranked and cranked with his new machine in hand, only to discover the machine was quickly emptied. Now broke and possessing only the clothes on his back and a useless contraption, Dominic was too old to work and forced to enroll in the local relief budget (welfare).

For the next decade, Dominic wandered in vain around the Civic Center looking for the two men who sold him the machine.

He reported his swindle to the Long Beach police, who turned over the investigation to their internal Bunco Squad, who, with few leads and little evidence, never found the con men1.

Police Bunco Squads formed as early as 1913 in US police departments

A money-making machine might seem far-fetched, but “Chumps are plentiful everywhere,” as the Long Beach Police told a reporter.

One early case reported in the San Francisco Call in June 1913 reported police corruption in the police Bunko Squad itself:

New testimony of a broader scope regarding police corruption in San Fran- cisco than any that has been secured since the beginning of the investigation into the bunko ring graft is promised through the expected return to San Francisco of Logiano Rovigo, youthful member of the gang, now in jail in St. Louis.

At issue was the charge of police corruption of Policeman Arthur Macphee and Charles Taylor, who conspired with a known “bunko ring” to free criminals against court orders for a fee.

In April 1933, the L.A. Bunco Squad, with the help of San Pedro Police, arrested Frank Stone, 37, and John Enright, 50, on grand theft for defrauding a local man of $1,700 in oil stock2.

At the urging of police, Hollywood produced a short film in 1938 to educate the public about the fraud of fortune tellers.

“Fortune-tellers sell knowledge they do not possess,” wrote Capt. Edwards of the LAPD. “But even this is not the worst phase of their racket. The real danger lies in the fact the advice they give is unwise and destructive.”

A reported $125 million a year was swindled from superstitious Americans in a wave the Buffalo Courier Express called “such as the world has not seen since the Middle Ages3.”

Bunco soothsayers, racketeers, and swindlers had developed a reputation and a profile in the mind of most Americans by the 1920s. After decades of Bunco parlors, most people had heard of the easy three-dice game even if they’d never been in one. Bunco’s social nature, quick rolls, fast-moving hands, ease of learning, and often free-flowing liquor meant loads of easy targets for con men looking to get people to bet big — and lose.

“The Bunco game is one of the oldest in the world,” wrote Elizabeth Brown from the LAPD in the Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet in May 1929. “Operating these schemes for the hoodwinking of the great American Public and cleverest crooks that the criminal world has to offer. They are certainly the most ruthless since they work entirely by gaining the confidence of their victims.”

She continues, “The men, from whose fertile brains these rackets evolve, are men of above average intelligence and smartness. In fact, to be successful they must be clever, or they are caught at the beginning of their despicable careers.”

Los Angeles police had a staff of 17 officers working their Bunco Squad into the early 1930s. Many Bunco men were indeed so good and earning the trust and confidence of their victims that it was the victims’ family or close friends who reported suspected “buncos.”

Many of the small-dollar buncos were too small to be investigated. But the police made every effort to investigate gold mine certificates, stocks, bonds, or business deals. Some were long-cons operating for weeks or months to garner a signature that would unload tens of thousands or even millions of dollars.

“It takes three to five years to train a [Bunco] officer,” says LAPD Captain Thomason. Bunco squads were trained to spot pickpockets weaving in and out of crowds, without revealing the location of the officers. Bunco squads trained to gather information from “skinned” victims and learn the “gags” of “buncos” who were operating in their area or reportedly heading their way4. Many of the buncos could be caught in 3-4 days.

In 1938, police in Greeley, Colorado, raided a dance studio that promised to train little girls to be the next Shirley Temple. Dozens of kids, ages 4-17, were waiting their turn to practice, rehearse, and “get a spot in a movie.” The families were charged $3 for a screen test and $10 for a dance test, or about $300 in 2024 dollars5.

The role of Bunco Squads in law enforcement

Bunco squads have long been in the fight against organized crime and fraudulent activities. These specialized units, composed of seasoned law enforcement officers, are dedicated to investigating and prosecuting cases involving confidence tricksters, con men, and other deceitful individuals who prey on unsuspecting victims.

One of the most notable examples of a bunco squad in action is depicted in the 1950 film “Bunco Squad,” where Detective Sergeant Steve Johnson takes on a ring of phony mediums. Johnson’s meticulous investigation led to the arrest and prosecution of several individuals involved in the scam, highlighting the lengthy, effort and role bunco squads play in protecting the public from fraudulent activities.

The San Francisco Police Department’s Bunco Squad, for instance, has been a formidable force since the early 20th century, earning a reputation as one of the most effective units in the country. Similarly, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Fraud Squad boasts a dedicated team of detectives specializing in bunko games and scams. The New York City Police Department’s Organized Crime Control Bureau also has a unit focused on investigating and prosecuting cases involving organized crime, including bunko schemes.

In today’s digital age, the work of bunco squads is more crucial than ever. With the rise of online scams and cybercrime, these specialized units don’t go by the same names anymore, but continue to adapt and evolve, ensuring they remain at the forefront of the battle against fraudulent activities.

Bunco squads fade in favor of more sophisticated investigative units

By the late 1960s, most police departments had stopped referring to their investigators as “Bunco Squads.” While the term persists in the minds of many people today, law enforcement detectives and investigators have become more specialized — like in domestic or child abuse units — or more generalized to investigate broader, more sophisticated crimes like public benefits fraud.

Today, you can catch your own Bunco online at PlayBunco.com. The social game has shed its shady past and become a popular, family-friendly way to spend time with others.

1. Nov 23, 1943, Page 13 - Independent

2. Apr 25, 1933, Page 16 - News-Pilot

3. Jul 17, 1938, Page 6 - Buffalo Courier Express

4. May 07, 1929, Page 4 - The Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet

5. Aug 20, 1938, Page 1 - Greeley Daily Tribune